The story of how Carolyn Sapp, Miss America 1992, became an accidental domestic violence crusader marks the moment that a new era for Miss America came into focus. The pageant had barreled out of the messy 1980s with still-formidable television ratings, a bulwark of corporate sponsorships, its identity in the public imagination secure, but also aspirations for a new relevance. Just in time for the advocacy-minded Miss Americas of Generation X.

More than 20 years after feminists protested on the Boardwalk, the first generation to enjoy all the fruits of the women’s movement was coming of age, and some of its members, as it turned out, were still interested in pageants. They would seize their crowns with more self-direction than the women who preceded them. And eventually, they would become the first group of Miss Americas to question why the pageant wasn’t controlled by Miss Americas—and set out to do something about it.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

It was 4 a.m., and Carolyn Sapp had barely taken the new crown off her head to catch a few hours of sleep when the phone rang in her Atlantic City hotel room. It was a reporter, from her home state of Hawaii. But instead of late-night congratulations, he was asking the new Miss America about Nu’u Fa’aola—her ex-fiancé, a former New York Jets running back and, until that night, the better-known half of their relationship.

“We know you had him [reported] for domestic violence,” the reporter said. “Tell us about it.”

Miss America had never dealt with a Miss America quite like Carolyn Sapp before. She looked like an old-school beauty queen from the 1940s, an hourglass knockout with the big shoulders and the big face and big hair, her natural strawberry blonde dyed a rich mahogany to set off her pale skin and dark red lips. (It was the ’90s.) But her energy was a very new thing. She had a swingy kind of walk and eyes that would pin you to the wall while her mouth stayed in constant motion, laughing, talking, smiling.

The night she was crowned, when they told her they needed a family picture, but just with your mom and dad, okay? Sapp pushed back, not for the last time, and got both her stepparents and her three half-siblings and a grandmother and a couple aunts and a cousin in the photo, too. The next morning, as she posed for photos in the surf, she let the Old English sheepdog who came bounding into the frame lick the makeup off her face, and the photographers nearly died of joy.

That energy could be a lot to take, and the Miss America staff didn’t always know what to make of it. They tsked-tsked when she greeted sponsors with a hug and a kiss, and she had to explain it was just the Hawaii way of doing business. The Carolyn Sapp way. But her sponsors loved it. They loved her, loved the fact that this Miss America was so much fun. She was always game to stay late, after the photos, after the dinner, to stay up talking and laughing, maybe even get up and sing with the band—you only have one year to be Miss America, right?—even as her dear pageant chaperone was left sitting there waiting at an hour when she would have much rather retired. There were clashes over this, too; high-level debates over the appropriate bedtime for a 24-year-old woman, though usually phrased in terms of how, “we don’t want you to burn out…”

But Carolyn Sapp and the Miss America Organization were on the same page in one important way, for which that extraordinary energy of hers would prove essential.

After that terrible, early-hours phone call from the reporter, she went to talk to Leonard Horn, the pageant’s longtime general counsel who was then also its chief executive. And she told her new boss everything about the private trauma that would soon explode into public view. Horn listened and made some lawyerly calculations.

“You have a choice,” he told her.

Read more: Inside a History-Making Protest With the Women Who Took on the Miss America Pageant

Sapp had beaten a field that included two professional opera singers, a Phi Beta Kappa concert pianist, a classics major and an attorney for the National Labor Relations Board. Carolyn couldn’t recall her Hawaii Pacific University grade-point average when someone at her first press conference asked her about it.

“I’m an average student,” she replied.

Journalists chalked up her victory to retrograde sensibilities. “The mob demanded a babe. It got one,” sighed the Washington Post. “She wasn’t just Miss Hawaii. She was Miss Ha-cha-cha,” the Philadelphia Inquirer hooted. “While the other contestants promenaded down the runway, Sapp slinked…. the sexiest [Miss America] since Vanessa Williams.” They couldn’t have known that Sapp had crushed it in her interview, with compelling stories about her sprawling multicultural family, her travels beyond Hawaii, the three jobs she’d juggled through college.

There were insinuations that Donald Trump, the Atlantic City casino owner, somehow had something to do with her win. He had nothing to do with it—a past judge, he merely swanned around the pageant that year with his fiancée, Marla Maples. At one pre-show gathering, he swaggeringly asked to see the “bodies” who had won the swimsuit competition. And Sapp, being Sapp, stepped forward with just as much swagger: “I don’t know if you remember me…?” she said. Everyone in the room took note.

(A couple years earlier, Carolyn had traveled to New York for a PR job, and the future president of the United States chatted her up. Nothing had happened, so she had no qualms about reintroducing herself. But her air of familiarity got pageant tongues wagging; Maples described her as “very brazen.” She and Trump broke up after that weekend in part because of his ogling commentary from the front row of the pageant, though they reconciled and wed two years later.)

Sapp didn’t seem bothered by this particular strain of gossip and media criticism. The story about Nu’u Fa’aola was looming, and it blocked out everything else.

She and Fa’aola had been the celebrity couple back in Honolulu. He was the hometown football hero who’d made it to the NFL. She was Miss Kona Coffee, Miss Waikiki, Miss Honolulu—corny-sounding titles that in fact had ushered her into rooms with politicians and CEOs and sent her across the Pacific to promote Hawaii tourism and business development in Japan. And for a while, everything had been fine. Well, sort of.

There were flares of temper, physical outbursts that she had trouble interpreting. At first, she found it oddly flattering: He must really like me if he’s this jealous! But more than a year into their relationship, Fa’aola was cut by the Jets and brooded angrily. As they walked through a park together, he abruptly turned his furor her way, hitting, kicking and threatening to kill her. It seemed so out of character, and he was so immediately apologetic, that Sapp blamed herself for not being supportive.

Months later, Fa’aola was cut by another team. They started quarreling in the car while he was driving; he tried to push her out of the moving vehicle and strangle her with the seat belt. Sapp broke off their engagement, but felt the need to remain friends, and one night in the fall of 1990, after she had given him a ride home, he assaulted her again, slamming her against a wall and threatening her with a knife. That’s when she got the police involved and filed for a restraining order. It was this filing that journalists would find connected to her name a year later, after she became famous overnight.

“You have a choice,” Leonard Horn recalls telling Sapp that morning after her crowning, when she told him everything: You either figure out how to talk to the media about the abuse in a productive way, or you opt not to talk about this at all. It wasn’t much of a choice, he acknowledged. Either way, they’re going to hound you.

She decided to talk.

If the press didn’t know what to make of Sapp, they really didn’t know what to make of domestic violence in 1991. Especially when experienced by a prominent woman. And especially when a prominent man stood accused. If the reporters who broke the news had any hesitation about exposing the identity of a victim of violent crime—which ran as counter to journalism standards then as now—this concern did not come across in the stories. “Miss America: old ex-beau troubles,” is how the Honolulu Advertiser wrote the front-page banner headline. Others referred to it as Sapp’s “stormy relationship.” Or even more darkly, her “troubled past.”

“There she is, the latest gossip topic,” chortled the headline on a story musing that “the Miss America pageant may have gotten more than it bargained for.” The fact that Sapp’s ex-boyfriend had beat her up got mingled in the media imagination with the unwarranted snark coming out of the pageant world—her GPA, the Trump thing, the photos dredged up from Hawaii of her “seductive poses” in “very tiny bikinis.” (“Bikinis are very popular and very necessary in Hawaii,” she responded dryly.)

A decade or so later, it became almost a rite of celebrity passage to come clean about childhood trauma or personal struggles; in the early 1990s, it was highly unusual to learn these things about a famous person, and those who were coming forward were often controversial or faded-fame personalities perceived to be desperate for attention. Sapp sometimes got lumped in with them, though she had never even volunteered her story.

“I felt like I was being punished in a sexual way for being a victim of domestic violence,” Sapp says. “I got a quick education in media.”

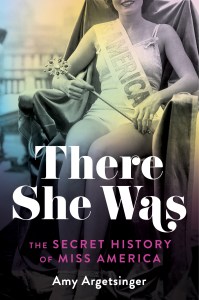

Excerpted from There She Was: The Secret History of Miss America, published by One Signal/Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Amy Argetsinger.

0 Comments