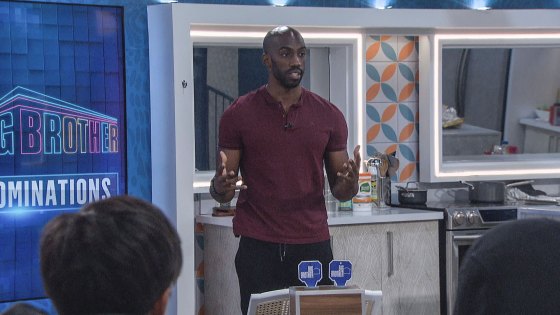

Fifty-six days into season 23 of Big Brother, six houseguests held a secret meeting in the bathroom. Secret alliances are nothing new in the CBS reality TV competition, but this one was different. The Cookout was the first major alliance composed solely of Black contestants; the group could never accomplish their mission—to ensure the show’s first-ever Black winner, whichever of the six of them that would turn out to be—if other houseguests were onto them. Hence, the clandestine water closet conference.

This scene was just one of many in an unprecedented season of Big Brother, which ended on Sept. 29 with The Cookout’s mission accomplished: Xavier Prather, a Black man, emerged victorious on finale night, taking home $750,000 and making history in a show that has long struggled with racism in its casting, production and interpersonal relationships.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Big Brother is one of America’s longest-running reality shows, which sees a group of “houseguests” sequestered together—and competing against each other—over a period of multiple months in competitions and interpersonal conflicts. Its format forces contestants to make (and break) alliances with their fellow players; each week, one (or more) is “evicted” thanks to a vote from their peers. For viewers it’s a choose-your-own-adventure show, with levels of involvement ranging from “casuals” who watch CBS’s edited show three times a week to “superfans” who watch the “live feeds” on Paramount+ for a 24-7, front-row-seat to everything. (Yes, that even includes when houseguests sleep or use the restroom).

The show’s casting has long relied on familiar archetypes—the surfer dude, the jock, the Southern belle—and whitewashed patterns. Prior to this year, Big Brother had consistently cast only a handful of minorities each season. Over 20 years and across 22 seasons, there had never been a Black winner, and only one of its last 11 seasons included even a single Black person among its final six contestants. This season diverged in large part because of both top-down casting adjustments mandated by the network and the subsequent game strategy of its diverse cast. And the impact of the season’s outcome has significance far beyond who went home with that big check.

“We generally write reality television off as a guilty pleasure or trash television, but I think that it really does reflect and refract society’s issues around diversity, inclusion and discrimination,” says Brandy Monk-Payton, a professor of media and black cultural studies at Fordham University. “A show like Big Brother has a real impact on American culture.”

Read more: The Bachelor Finally Cast a Black Man. But Racism in the Franchise Has Overshadowed His Season

A history of racism on the show

Both fans and critics of Big Brother have long flagged its problems with racism and bias, whether in regard to its casting and production, its curation of an edited TV narrative (which has often traded in stereotypes) and in the behavior of its individual houseguests themselves. And in recent years, former players have also begun speaking out too—Kemi Fakunle, a houseguest on Big Brother 21, has said in interviews that she felt she was targeted because of her race. (Big Brother 21 featured six non-white players, four of whom—including Fakunle—were eliminated in the show’s first three weeks.)

Many of the most memorable incidents of racism took place in 2013 during the show’s fifteenth season, which took the then-rare step of including problematic behavior caught on the show’s live feeds in its TV edit. A number of white contestants made racially motivated comments and were widely judged as bullying the sole Black woman who had been cast that year; at one point houseguest GinaMarie Zimmerman said of the woman, “[she’s] on the dark side, but she’s already dark.” Houseguest Aaryn Gries then replied, “Be careful what you say in the dark, might not get to see the bitch.” In separate incidents, Gries and others made anti-Asian remarks about the Korean-American contestant in the cast.

During season 4, a decade earlier, producers had included an anti-Korean slur from Erika Landin in a diary room session, during which contestants provide thoughts and emotions regarding the events taking place in the house. The winner of that season ended up being Jun Song, who is Korean American; Landin’s slur was directed, in fact, at Song’s ex-boyfriend. (The season featured a casting “twist” described as the “Ex-Factor,” and saw contestants like Song competing alongside former partners.) Song’s victory made her the first person of color to claim the winner’s title; it would be another 14 years before the next person of color was crowned when Josh Martinez, who identifies as Latino, won season 19. “I think I was naive thinking it would happen sooner. I didn’t think it was going to take that long,” Song tells TIME. (Prior to Prather’s victory, there had been three non-white winners total: Song, Martinez and Season 20’s Kaycee Clark, who identifies as Southeast Asian. Tamar Braxton, who is Black, had also won a special celebrity edition of the show.)

Song acknowledges that, within the minority groups of the house, Black contestants have historically gotten the short end of the stick. (In her season, the sole Black houseguest was voted out first.) Danielle Reyes, a Black woman known as the “greatest winner to never win,” lost the third season after her eliminated houseguests returned on finale night to “bitterly” cast their vote for the less-strategic final-two choice after getting to see Reyes’ ruthless gameplay and confessionals from home. Viewers speculate show producers knew Reyes, who dominated the season, deserved the win, as they created the jury for subsequent seasons, in which eliminated houseguests starting on week six are sent to a different sequestered house for the remainder of the season. Song credits the formation of the jury, due to Reyes’ infamous loss, as one of the main reasons she was able to win.

Da’Vonne Rogers, a fan-favorite houseguest (and superfan herself), was unapologetically vocal about the history of Black houseguests becoming early targets in the game. After participating in Season 17 and being sent home pre-Jury, Rogers returned for Season 18 and a highly-anticipated All-Stars season in 2020. Five weeks into her third appearance on the game, houseguest Christmas Abbott would nominate Rogers for eviction alongside her “Black Girl Magic” partner, Bayleigh Dayton. When tensions rose, Rogers had to not only consider how her responses would be perceived by the majority-white houseguests who held her game’s fate in their hands, but to viewers at home.

“I hate this game,” Rogers said on live feeds. “Why does she [Abbott] get to talk to me like that, but if I respond everybody’s gonna look at me crazy?” Black contestants feeling pressure to avoid falling into various tropes like the “angry Black woman or man” is a dilemma many in the reality space face, according to Monk-Payton. “It’s a very real concern that contestants of color have on these different programs. They have to be attentive to how audiences might perceive them while navigating within the gameplay itself,” she says of Black contestants’ double consciousness.

On eviction night during the All Stars season, Rogers had an opportunity to make a plea for her fellow houseguests to keep her on another week. Instead, she used her air time to send a larger message to millions of viewers at home: “[I’m] still screaming [for] justice for Breonna Taylor and every other Black life that has been taken unjustly and unfairly simply because of the color of their skin,” she said on live television. “All lives can’t matter until Black lives matter, and that includes Black trans lives as well.” Moments like this helped generate momentum for an alliance like The Cookout to eventually form, with several houseguests this season referencing Rogers as a driving force for their mission.

Read more: ‘This Is Hate.’ Bachelor Contestants Are Speaking Out About Racism, Harassment and Cyber Bullying

The most successful alliance in the show’s history

Iconic duos and large alliances have steamrolled the game before—think The Brigade in season 12 or The Hitmen in season 16, both of which were made up of primarily white men—but none have come close to the effectiveness of The Cookout. Formed in week one of the game, the alliance consisted of the six Black houseguests: Azah Awasum, Derek Frazier, Hannah Chaddha, Kyland Young, Tiffany Mitchell and eventual winner Prather. Their group had a mission “for the culture” that went beyond merely securing the cash prize: securing the show’s historic first Black winner. (This in turn meant many of the group prioritized their collective goal over their individual gameplay—even when they did not see eye to eye or even get along.)

While the group had its sights set on the finale, they’d already made history in Week 9 of the 12-week game when they became the show’s first alliance to get all of its members to the end. “I feel like most people can agree that The Cookout has become the best alliance in the history of the show,” says Taran Armstrong, live feeds correspondent for Rob Has a Podcast, who has watched every season since he was 9. “I don’t think there’s really much of a debate.”

But getting all six there unscathed was no small feat. In a house filled with people with nothing but time to strategize, their success required keeping their alliance a secret to avoid becoming a target. Making sure others in the house didn’t connect the dots also meant falsely pairing themselves with others outside the alliance and avoiding meeting as a group at all, instead opting to strategize with a weeks-long game of telephone with one another—a visibility factor that many powerful alliances in the past did not have to be as concerned about because they skewed white in a house that was largely white to begin with.

Christian Birkenberger, a Big Brother 23 houseguest who was evicted during week four, admits he had no idea about the alliance while in the house. “I’d never seen them collectively communicate with each other so I was just absolutely shocked when I found out that they were working together,” he says. “I had about four alliances blow up in my face and we all met every single day, so the fact that they did it with such little communication and they were on the same page was incredibly impressive.” It wasn’t until Day 56 —nearly three quarters of the way through the game—that the group would sneak into the house’s bathroom at 3 a.m.to meet collectively for the first time.

When the group reached the final six, a new chapter of the game began. Now the remaining three women and three men would need to start competing with one another to be crowned Big Brother’s first Black winner. It was ultimately Mitchell, who masterminded the alliance’s strategy, who would be the first to get evicted—a consequence, perhaps, of the sacrifices she chose to make for the success of the broader alliance. Many fans took to social media to voice their frustrations about what has come to be a pattern of strong female strategists on the show not getting the win. “It’s so disheartening that a season that finally addressed the racism that has run rampant on this show from the beginning is being marred by blatant misogyny in the end game,” tweeted long-time fan Lisa Bee. Nearly 70% of the show’s winners have been male, and it wasn’t until 2018 that the jury voted for a woman to beat a man in the final two chairs for the first time.

The dynamic of this season’s cast and the relationships that ensued prompted several other complex conversations regarding identity. Dialogue ranged from whether Chaddha, who is biracial, should be included in the all-Black alliance, to Mitchell asking Asian-American houseguest Derek Xiao what race he considered himself, to Latina houseguest Alyssa Lopez questioning where she stood on the chopping block as someone who was not Black, but identified as a minority. While many of these conversations took place during live feeds as opposed to broadcasted episodes, they marked a major increase in the frankness with which race was addressed on the show.

The power of the production

Big Brother has been running under the leadership of executive producers Allison Grodner and Rich Meehan since its seasons in the early 2000s. But this season’s victory can’t be discussed without acknowledging major changes in Big Brother’s casting process. Robyn Kass, who cast every season for the last 20 years, was recently replaced by casting director Jesse Tennenbaum after departing the show for what she described on Twitter as “some big opportunities.” Last November, CBS announced an initiative that would require their network’s reality TV programs, including Big Brother, Survivor and Love Island, to have 50% of their casts identify as Black, Indigenous or People of Color (BIPOC).

Outside of casting, there have also been frustrations around the show’s confessional “diary room.” Viewers have suspected producers of intervening, causing the entries to appear less natural. Fakunle, of Season 21, said on live feeds that she was encouraged to use a stereotypical Black accent by a producer for a diary room soundbite. And while live feeds offer superfans an unfiltered look at the houseguests’ gameplay and interactions, in the end, the majority of viewers see storylines that have been filtered and shaped in an editing room at the discretion of producers. This fact has long been a point of contention across reality TV: who is getting the “villain edit,” who is selectively made to appeal to viewers, and how do these decisions, consciously or subconsciously, align with the race of contestants?

Song says a lot of her fellow show alumni over the years have been afraid of being vocally critical for fear of not being invited back to participate in future cameos or All Stars seasons. “A lot of the Big Brother alum[s] have chosen to turn a blind eye and to play Switzerland,” says Song. “The silence is really deafening when it comes to matters of diversity and inclusion in reality television and in the workforce.” She also points to the show’s consistent viewership numbers and interest from advertisers as reasons why there has long been a lack of urgency to address the house’s diversity issues any sooner.

Not everyone was happy about the outcome of this season, with many of the show’s audience members alleging reverse racism of The Cookout’s strategy. “It speaks to the audience demographics of these programs and how fans themselves have had a very critical role to play in the popularity of these programs,” Monk-Payton says. “I think it’s easy for some fans to say Black contestants were segregating and colluding with one another without seeing the flip side of contestants of color being consistently marginalized in the franchise and that the [Cookout] alliance was a means of empowerment to ensure equity in the competition.”

For many BIPOC viewers who saw themselves represented in this year’s cast for the first time, this season was a step forward, but also a call for the industry, and other popular reality shows like The Bachelor franchise, to do better when it comes to including and recognizing people of color among their casts. “I’ve talked to fans of the show who were literally in tears talking about how much this season meant to them,” says Armstrong. Now future houseguests and viewers will anticipate what this unprecedented season could mean for next season’s casting, house dynamics and gameplay strategy—and how it might even help change the landscape for reality television.

0 Comments