When Quito entered lockdown in March 2020, the streets of Ecuador’s hilly Andean capital didn’t quite empty out. A small army of cyclists and motorbike drivers, wrapped in brightly colored jackets, continue to zoom around the city, ferrying goods for popular food-delivery apps. As in many countries, delivery drivers were considered essential workers and allowed the same dispensation as health workers to move around.

But drivers say they that essential status doesn’t carry through to their treatment by authorities, society or the companies that control the apps. “We are helping society because people don’t want to go out right now—when you don’t want to go, we’re the ones who go,” says Yuly Ramirez, a Venezuelan migrant who started working as a delivery driver for Glovo, one of the region’s biggest platforms, in 2018. “But instead of seeing us like that, they see us as a nuisance.”

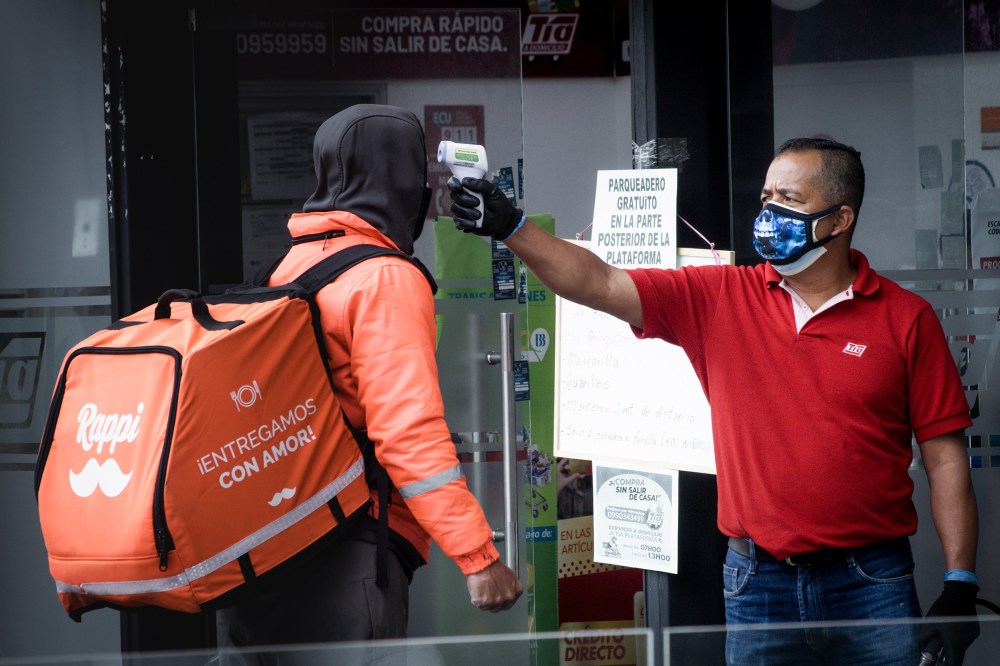

The pandemic has thrown new light on a long-simmering battle between drivers and the delivery platforms in Latin America. Ever since early 2019, when apps—including Colombia’s Rappi, Brazil’s iFood and U.S.-owned UberEats—exploded in popularity across the region, workers in major cities have been protesting low wages and a lack of job security, labor rights and safety support.

Read More: The Coronavirus is Cutting Into Gig Worker Incomes as the Newly Jobless Flood Apps

Companies say that their delivery drivers are contractors rather than employees, and that the flexibility of the arrangement benefits everyone. Gig-economy workers in the U.S. and Europe work under similar kinds of contracts and have voiced similar concerns. However, in Latin American countries including Ecuador, Colombia, Argentina and Chile, the boom in apps has coincided with the movement of millions of migrants from crisis-stricken Venezuela. This, combined with the prevalence of informal work and precarious jobs in the region’s labor markets, means that the delivery drivers tend to be some of the most vulnerable members of society.

The number of both customers and drivers during the pandemic has grown, thanks to restrictions on movement and job losses in other sectors. So too has frustration among drivers, says Ramirez, 37. A mother of four, she trained as a lawyer in Venezuela before moving to Ecuador in 2017, becoming one of the roughly 445,000 Venezuelans now living in the country, out of 5.6 million spread across nations in Latin America and the rest of the world. As well as the threat of COVID-19 infection and precarious working conditions, Ramirez says she and her co-workers face the xenophobic abuse reported by Venezuelans across the region. But politicians and authorities have offered little support, she says, with sparse attention paid to Ecuador’s growing crowd of gig-economy workers in the campaign for the April 11 presidential elections.

On April 1, a court in Quito held the first hearing on a lawsuit brought by Ramirez against Glovo, which has now rebranded in Ecuador as PedidosYa after Glovo sold its Latin America operations to European multinational Delivery Hero in September. The suit, the first case against Glovo in Ecuador, argues that it has violated constitutional labor rights to decent work, fair pay and rest breaks. The court ruled against Ramirez, saying that she had knowingly accepted the conditions when she started working for Glovo, and that her case was a contractual matter, not a constitutional one. She is appealing.

“The companies use their contracts as camouflage to claim we’re autonomous, but it’s not true,” Ramirez says. “We have to do everything they say, when they say, and we are working 10 hours a day, with no safety net. It’s like we’re machines to make them money.”

Glovo has not yet responded to TIME’s request for comment. Delivery Hero declined to comment on Ramirez’s case, but said in an emailed statement that the company makes sure that drivers “get compensated in a fair manner” and that “the safety of the rider community is a priority.”

In the past three years, delivery apps have rapidly become a vital source of work for thousands in Ecuador and the rest of Latin America. As the apps came online in the late 2010s, they met a far more established culture of food delivery than they did in Europe, says Elva López Mourelo, a Buenos Aires–based specialist in inclusive labor markets at the International Labor Organization (ILO). It has long been normal for even small restaurants and shops to offer deliveries in some Latin American countries. The apps’ cost-saving practice of treating drivers as contractors quickly disrupted existing delivery companies that employed full-time drivers. Some large delivery companies pivoted to copy the apps, and app-based gig-economy-style delivery became the norm for food delivery in many Latin American cities, triggering a growth of almost 400% in home food-delivery sales over the past five years, according to a 2020 report by market researcher Euromonitor.

Despite the challenges of the gig economy, the apps are very attractive for many workers, according to López Mourelo. Migrants like those from Venezuela face hurdles in seeking other types of work but, in some countries, can start earning money with the apps “almost immediately” after arriving in a country because of the flexible form of the contracts. And even for those who have lived in the same country all their lives, the precarious and informal nature of the labor market means that working for the apps is often preferable to the exploitation they could face working for “a single person controlling their employment and keeping them off the books,” López Mourelo says. (Fifty-five percent of workers in Latin America, or 140 million people, work in the informal sector, according to the Inter-American Development Bank.)

But the work is not easy. A study published March 30 by international labor-research group Fairwork found that six of the largest gig platforms in Ecuador—Uber, Cabify, Glovo, Rappi, Encargos y Envios, and Ocre—scored from 1 to 3 out of 10 on its criteria for measuring fair labor conditions, including reasonable pay, transparent contracts and safety protocols.

Ramirez says the “contractor” status that companies give to their drivers creates a false impression of autonomy. According to a report by the German nonprofit Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 68.7% of drivers for delivery apps in Ecuador work seven days a week, for an average of 10 hours a day, and face limits on choosing their shifts.

Ramirez also says she often faces hostility from Glovo customers and restaurant staff if they realize she is Venezuelan. Despite a 2019 presidential decree granting Venezuelans the right to apply for humanitarian visas, Ecuadorean authorities acknowledge they have struggled to stop xenophobic sentiment against Venezuelans, who report episodes of violence, labor discrimination and a negative portrayal of their community in the media. “People see us as their servants. We’re not preparing the food, but people get angry with us because the sugar didn’t arrive or there’s onion on their burger,” Ramirez says. “They say, ‘You’re Venezuelan, you’re useless,’ or ‘You came to the country to cause trouble’—so many ugly words.”

When COVID-19 began to spread through Latin America—with Ecuador becoming an early hot spot last spring—drivers’ concerns grew. Initially, drivers for Glovo said they were not provided with personal protective equipment to prevent them catching the virus, or with alcohol gel or a place to wash their hands during shifts, Ramirez says. (Glovo told local media last April that it was in the process of rolling out masks and antibacterial gel for drivers.) And while Glovo celebrated a 300% growth in its user base in Ecuador by November, the number of new drivers joining the company, as jobs in other industries disappeared, made it hard for all drivers to keep earning enough money to get by.

Protests began before the pandemic but have intensified in the past year. In Quito, Ramirez and her co-workers started striking in November 2019, after Glovo lowered the rates paid to drivers, arguing that they would be able to earn more thanks to the app’s growing popularity. During the pandemic they have staged more strikes, with thousands of drivers across the city disconnecting from the app at once. Hundreds have participated in street protests outside Glovo’s offices, demanding better pay, working conditions and safety protocols. Ramirez says protest coordinators had a brief “dialogue” with Glovo’s head of operations last year but have received no “positive response” to these demands.

They are far from alone. In São Paulo and other Brazilian cities, thousands of drivers joined in motorcades in July to protest working conditions set by Uber. In Bogotá, around 1,000 drivers for Rappi congregated outside the labor ministry to put pressure on the government to regulate the apps. Last April and October, protests stretched beyond individual cities or countries, as drivers for apps all over Latin America coordinated to strike on the same day.

Across the region, the protests have secured some victories, López Mourelo says, with some companies introducing compensation schemes for drivers who catch COVID-19 and are unable to work. Others have changed their policies around the provision of backpacks and other equipment, and others have raised salaries.

Globally, top courts are where workers’ rights activists have achieved their biggest impact on the gig economy. In September, Spain’s supreme court ruled that Glovo is, in fact, an employer of its drivers, and not just an intermediary between drivers and restaurants, as the company had claimed. In February, in a ruling against Uber, the U.K.’s supreme court ruled that its drivers are workers, entitled to a minimum wage and rest breaks, among other rights. Cases in Latin America have not yet made it to supreme courts. But in November, a court in Chile found that a driver for PedidosYa was an employee, ordering the company to pay him compensation for unfair dismissal.

Those rulings have helped trigger efforts by lawmakers to regulate delivery apps. In March, Spain announced it would become the first E.U. country to amend its laws to protect gig delivery workers and give them rights like collective bargaining. Lawmakers in Peru, Chile and Colombia are all considering legislation that would grant more rights for gig-economy workers. López Mourelo expects a “chain reaction” across the region after the first country passes a law.

Regulation to support app delivery drivers does not exist yet in Ecuador. But developments in Spain and other Latin American countries have made Ramirez hopeful that her lawsuit and others like it will eventually force authorities to act. “At the moment, it’s hard because no one is looking out for us,” she says. ”But I don’t feel bad. They’ve won in other countries. And I know we will win here.”

Isadora Romero is a photographer based in Ecuador. Her work is supported and produced by the Magnum Foundation, with a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation.

0 Comments