More than three decades after the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the first World AIDS Day on Dec. 1, 1988, the world’s leading global health organization faces another public health crisis in COVID-19. On this World AIDS Day, those who raised awareness of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, find devastating similarities and haunting differences in America’s response to both crises.

In 1981, scientists recorded the first cases of a rare pneumonia, usually found among immunosuppressed patients, among a group of gay men in Los Angeles, and noticed more cases appearing among gay men in San Francisco and New York City, as well as cases of the rare cancer Kaposi sarcoma. In 1982, the CDC gave those cases a name, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and scientists confirmed the virus that causes it, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), in 1984. AIDS patient deaths in the U.S. steadily rose from 122 in 1981 to more than 50,000 at the peak of the AIDS epidemic in the U.S. in 1995. Since the beginning of the epidemic, about 75 million worldwide have become infected with HIV, nearly 38 million are living with it today—including roughly 1.2 million in the U.S.—and about 32 million people worldwide have died of AIDS-related illnesses, according to the United Nations.

From the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, comparisons have been drawn between it and the spread of AIDS. Many have pointed out the stark public response differences between the two outbreaks and how the lag in outcry over the deadliness of AIDS cost lives.

“The people who were suffering from HIV and AIDS, especially in the early days, were shunned,” says Henry Waxman, a former congressman from California who chaired a House subcommittee on Health and the Environment in the early days of the AIDS epidemic (and who is not related to the author of this TIME article). “When we found out about this disease, we didn’t even know its name because no name had been given to it, but it affected gay men primarily, was geometrically multiplying with people, [among] people who didn’t want to talk about it, because of the those who were involved, who suffered from it. and those people who are gay men faced a very different situation in the early ’80s than they do now… [The COVID-19] pandemic, as awful as it is, is a very different situation. We had trouble getting money to do anything to fight back against the AIDS epidemic, but we’ve had no problem at all getting money to fight back against COVID, which is, is a very good thing.”

Curran says the initial federal response to AIDS was hindered by “neglect,” but not any kind of White House attempts to interfere with the data that the CDC publishes. “If the CDC had important information, it was never modified.”

“Public health is always political, but shouldn’t be partisan during a pandemic,” says Curran. “It’s political because you have a new problem occurring, and you have to get all of the populations engaged in dealing with it.”

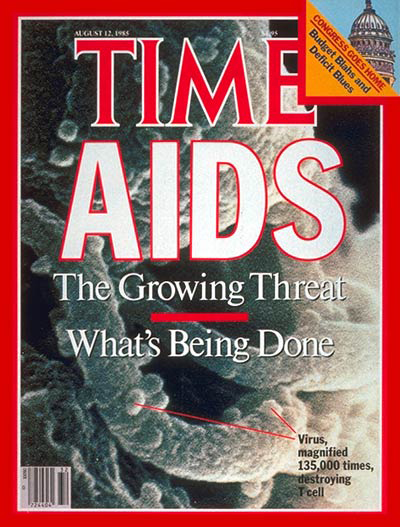

In contrast to 2020’s almost round-the-clock media coverage of COVID-19, it took a high-profile celebrity case to make the general population realize how widespread HIV/AIDS was becoming. The first major turning point in AIDS awareness came on July 25, 1985, when actor Rock Hudson, a friend of the Reagans, revealed he had AIDS, and died two months later. President Reagan began to take this public health crisis more seriously after learning of Hudson’s diagnosis, a former physician of Reagan told the New York Times in 1989. As TIME described the dramatic shift in mainstream public perception on HIV/AIDS in the Aug. 12, 1985 issue:

[I]t was the shocking news two weeks ago of Actor Rock Hudson’s illness that finally catapulted AIDS out of the closet, transforming it overnight from someone else’s problem, a “gay plague,” to a cause of international alarm. AIDS was suddenly a front-page disease, the lead item on the evening news and a frequent topic on TV talk shows. There seemed no end to the reports.

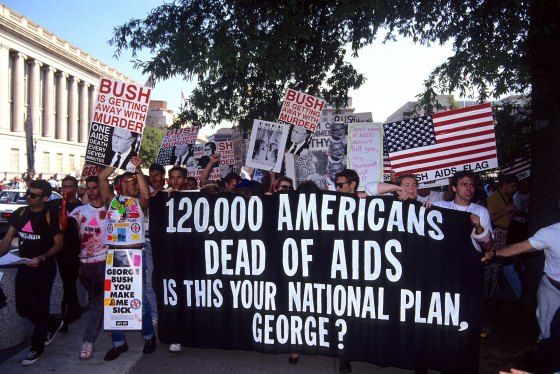

AIDS patients and advocates in groups like ACT UP also aimed to draw attention to the climbing death rate through bold actions, from spreading the ashes of AIDS victims over the White House lawn and organizing funeral processions carrying the bodies of AIDS victims.

And yet, it was a non-celebrity AIDS victim who spurred the landmark legislation of the peak of the AIDS crisis after nearly a decade of resistance to federal funding for AIDS research: The death of 18-year-old hemophiliac Ryan White on April 8, 1990, six years after making headlines in 1984 for contracting AIDS through a blood transfusion. Ronald Reagan, who didn’t publicly mention AIDS until 1985, four years into the crisis, eulogized Ryan White in the Washington Post. Then-Atlanta congressman John Lewis told the New York Times, “There is no way we can go around anymore saying this is an issue just affecting the gay community. In recent days, the life and death of Ryan White brought it home to many, many people.”

Four months after the teen’s death, President George H.W. Bush signed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, the largest federal HIV care and treatment program. The AIDS crisis also is one factor that led to landmark legislation the Americans with Disabilities Act signed by President George H.W. Bush a month prior in July 1990.

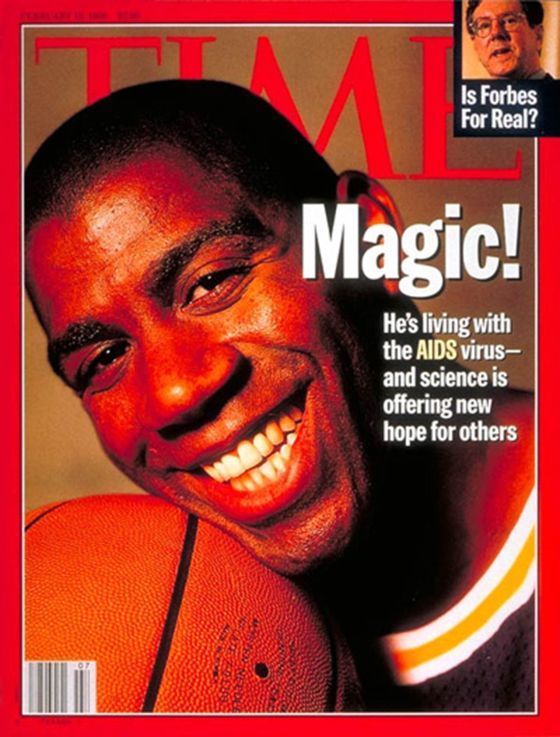

The 1990s saw key breakthroughs in treatments and public health awareness campaigns. After L.A. Lakers star Magic Johnson revealed in 1991 that he contracted HIV through unprotected heterosexual sex “made a difference” in terms of underscoring the seriousness of the threat of contracting HIV in the heterosexual population. FOX Broadcasting became the first national broadcaster to accept paid condom ads as long as the spots emphasized the health benefits and not birth control. Most importantly, in 1995, scientists discovered that a combination of drugs enables HIV patients to live a near-normal lifespan, and those regimens were made available to HIV/patients the following year. In 2019, there was a 23% decline in new HIV infections since 2010. But there is still no vaccine, and no cure, and AIDS still disproportionately affects Black and Latino populations.

World AIDS Day has become an annual occasion to remind the world that the AIDS epidemic is not over. Advocates hope that when the COVID-19 pandemic ends, people won’t forget the AIDS epidemic is still ongoing.

No matter the disease or population or differing levels of stigma, “the principles are the same,” Curran says. “What you need to do is have the best, transparent, scientific information and have it be updated all the time. You have to have consistent messaging, and you have to have trusted people on both sides giving the messages.”

With reporting by Suyin Haynes

0 Comments