A new strain of COVID-19 reported in the United Kingdom has been blamed for a sharp uptick of cases—prompting new lockdowns in London and more than 40 countries to ban cross-border travel from the U.K.

Although scientists say there is no evidence that the new strain is more deadly, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it could be up to 70% more transmissible than others, while the health secretary said it was “getting out of control.”

At least 40 countries including the entire European Union and Canada have temporarily banned incoming travel from the U.K. as of Monday.

And the new strain has been detected in Denmark, Australia and Gibraltar, according to the British government; and in Italy and the Netherlands, according to media reports.

But the U.S. has so far not stopped incoming travelers from the U.K. or Europe—sparking fears it may have already crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

“Today that variant is getting on a plane and landing at JFK,” said New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Dec. 20, referring to New York’s busiest airport. “How many times in life do you have to make the same mistake before you learn?”

Here’s what to know about the new strain of the virus.

What do we know about the new strain of COVID-19?

The strain was first detected by scientists in early December, according to the U.K. Health Secretary Matt Hancock. He first announced it on Dec. 14, saying that it was prominent in areas where the virus was spreading faster than expected.

Retrospective analysis found the strain was first present in the U.K. as early as September, according to the government.

By Dec. 19, scientific advisers to the U.K. government said they had “moderate confidence” that the variant was more transmissible than others, based on several factors including the exponential increase in infections despite lockdown measures. Genomic data suggests transmissibility that is some 71% “higher than other variants,” said a summary released by the U.K. government advisers.

Researchers now believe a mutation to the genes that code for COVID-19’s spike protein, the part of the virus that clings to human cells allowing for infection, likely causes its increased transmissibility, according to a study published Dec. 18.

However, what scientists know about mutation in SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—is still evolving, as they collect more samples of the virus from cases around the world. The ongoing research means studies are leading to conflicting results about whether specific genetic changes are helping the virus to spread more easily, or cause more disease. In a Nov. 25 paper published in the journal Nature, for example, scientists studied more than 12,000 mutations of SARS-CoV-2 from viruses in 99 countries and concluded that none were more easily spreading from person to person.

Read more: Inside the Global Quest to Trace the Origins of COVID-19—and Predict Where It Will Go Next

Will vaccines still work against the COVID-19 variant?

Officials said vaccines are still likely to work against the new variant, but that more research is being done to confirm this is the case. “The working assumption is that the vaccine response should be adequate for this virus, but we need to keep vigilant about this,” the U.K.’s chief scientific adviser Patrick Vallance said.

“There is still much we don’t know,” Johnson said. “While we are fairly certain the variant is transmitted more quickly, there is no evidence to suggest that it is more lethal or causes more severe illness. Equally there is no evidence to suggest the vaccine will be any less effective against the new variant.”

Still, because the current leading vaccines rely to some extent on targeting the spike protein, this mutation could be the first step in the virus becoming resistant to the current vaccines. “This virus is potentially on a pathway for vaccine escape, it has taken the first couple of steps towards that,” Professor Ravindra Gupta, professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute of Therapeutic Immunology and Infectious Disease, told the BBC. “If we let it add more mutations, then you start worrying.”

The U.K. began administering the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech on Dec. 8, following regulatory approval.

What’s happening with cases in the U.K.?

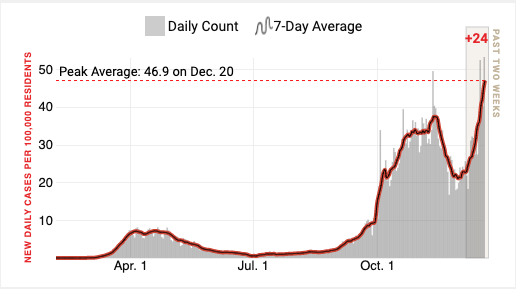

Daily confirmed cases in the U.K. hit new records over the weekend.

On Sunday, 36,000 people in the U.K. tested positive for COVID-19—the highest one-day total yet recorded, and double the daily figures from earlier in the week. The number of people in the hospital is rising, and at the highest level since April.

The spike comes despite several large swathes of the U.K. being under restrictive lockdown measures, with many businesses in some areas closed and people prevented from meeting indoors.

Those measures looked to have caused a decline in daily new cases in late November. Government scientists say the new strain has driven the recent spike.

Over the weekend, the U.K. government has placed London and the southeast of England into a new, restrictive “Tier 4” lockdown in response to the threat, forbidding people from traveling or meeting others over Christmas. The government had earlier said it would relax rules against groups meeting indoors over the Christmas period, despite calls from epidemiologists and opposition parties to think again. But as cases continued to rise in December, Johnson came under increasing pressure to change course, even as many families around the country planned to travel to see loved ones after a difficult year of isolation.

As recently as Dec. 16, the Prime Minister had rejected calls for the rules to be tightened, accusing his opponents of wanting to cancel Christmas. (In the rest of the U.K., families will still be allowed to meet indoors, but only for Christmas Day instead of the five days over the festive period that had been allowed earlier.)

Although experts say there is no evidence the mutation makes the virus any more or less deadly, an increase in people with the virus could result in hospitals becoming overwhelmed.

“As numbers increase in the community, you will always have a proportion of people who will end up in hospital. If those numbers increase, the pressure on your hospitals increases because the background pressure on your hospitals is so high,” says Dr. Catherine Moore, a consultant clinical scientist at the Wales Specialist Virology Centre.

That could lead to an increase in the death rate if there are shortages of trained medical staff available to treat them. “It doesn’t have to be more severe to be a problem,” Moore says.

How has this impacted travel?

At least 40 countries have now banned travel from the U.K. in light of the news about the new strain of the disease.

But travel to the U.S. from both the U.K. and Europe is still allowed for American citizens, per Trump Administration rules in place since March.

Right now, there are six flights per day into New York from the U.K., according to NBC New York.

The U.K. newspaper The Telegraph cited aviation industry sources on Dec. 18 saying that the Trump Administration was planning to pass an executive order as early as Tuesday that would lift the ban on non-U.S. citizens arriving from the U.K. and Europe. The news from over the weekend may affect those plans.

Within the U.K., there were scenes of chaos at train stations in London on Dec. 19 as people rushed to travel before new rules came into force. Many trains out of the capital were sold out, the Guardian reported.

The government has now said people in London and the southeast of England, where cases are highest, must not meet others over the holidays.

— With reporting by ALICE PARK/NEW YORK

0 Comments