As soon as Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were projected to win the 2020 presidential election on Nov. 8, women headed to Susan B. Anthony’s grave in Rochester, N.Y., to pay homage to the most famous American advocate for women receiving the right to vote. The suffragist is buried about an hour away from Seneca Falls, N.Y., the site of a women’s rights convention on July 19-20, 1848. It’s a meeting that American schoolchildren often learn is the birthplace of feminism and the start of the women’s suffrage movement.

But what many American schoolchildren don’t learn is that Susan B. Anthony was also fighting to ensure Black men didn’t get the right to vote before white women, that many suffragists excluded Black women from their events and that the fight for voting rights began much earlier.

Anthony promoted a predominantly-white history of voting rights activism, which is often believed to have ended in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was ratified, prohibiting states from restricting who can vote based on sex. In fact, Seneca Falls didn’t become known as the origins of the women’s rights movement until the 25th anniversary of the meeting in 1873, suggesting that crafting an origin story for the movement was not a priority before then, argues Lisa Tetrault, historian and author of The Myth of Seneca Falls:

Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898. Though Anthony is often reported as being at the 1848 Seneca Falls meeting, she was not. It was a local affair, organized in a few days by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and attended by around 200-300 white men and women. The only African American in attendance was abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

By beginning to tell the history of the suffrage movement as starting at Seneca Falls, Anthony and Stanton tried to show that the movement had a long and distinguished history, according to Tetrault, as damage control for the jailing of provocative suffragist Victoria Woodhull, while she tried to run for President in 1872.

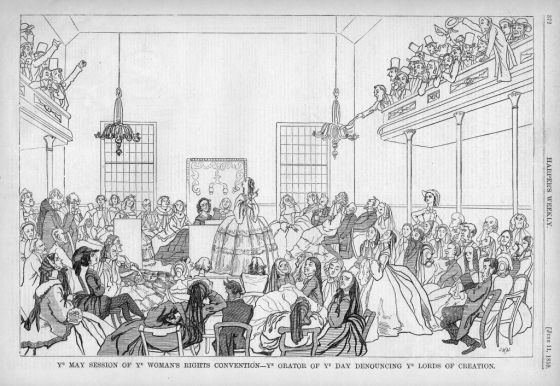

Starting the movement’s story then also allowed them to leave out suffragists who didn’t go to Seneca Falls and who they had fallen out with, at a time when there were internal disagreements between suffragists about the best way to achieve full equality for women in American society. For example, Lucy Stone was not at Seneca Falls, but organized what’s considered the first national women’s rights convention in Worcester, Mass., in 1850. Stone believed a state-level approach to women’s suffrage would be most effective way to guarantee women the right to vote, as opposed to amending the U.S. Constitution. She was also one of the white suffragists who supported the 15th Amendment prohibiting states from restricting voting based on race. Anthony and Stanton opposed the amendment because they did not think Black men should get the vote before white women.

“Emancipation is the new reality. And many people are saying to women, ‘Black men’s right to vote must happen now for reasons of free people’s safety.’ And Stanton and Anthony will say ‘no, women’s suffrage should come first,'” Tetrault explains. “And they are unusual in the women’s rights coalition that they demand this. They’re staunchly opposed to Black men voting before white women — in unspeakably racist terms.”

For African American women, for example, Tetrault says the meeting “was not a particularly important moment…Nor were the demands that they made particularly germane to the lives of women living under the twin oppressive forces of racism and sexism.”

Stanton and Anthony further cemented Seneca Falls’ place, and their own place, through the History of Woman Suffrage, a set of six-volumes boasting more than 5,700 pages. The book, however, long considered the definitive history of the 19th century suffrage movement, left out many Black voting rights activists.

Starting the history of the voting rights activism at Seneca Falls leaves out the earlier roots of Black women’s voting rights activism. Martha S. Jones, historian and author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, has traced it back to the 1820s and 1830s. While Black women were not included at the 1848 Seneca Falls meeting, they were in Philadelphia that spring fighting to be allowed to be licensed preachers. Formerly enslaved upstate New Yorker and activist Sojourner Truth represented Black women at the 1850 national women’s rights convention, and her “Ain’t I a Woman” speech the following year framed voting rights as human rights that galvanized generations of voting rights activists.

If the history of women’s rights starts at Seneca Falls, Americans “might have the misimpression that African American women weren’t interested in women’s rights,” as Jones puts it. “By 1850, Sojourner Truth is very much a presence in women’s rights circles, really shaping the debates. But she didn’t begin at Seneca Falls at all.”

In fact, white suffragists excluded Black women from many of their events, even making them march behind white activists at parades in the early 20th century. After the ratification of the 19th Amendment, many white suffragists groups disbanded, leaving Black women on their own to continue fighting the obstacles to voting: violence, voter intimidation, lynchings and more.

State laws passed in the Jim Crow era to get around the 15th Amendment and 19th Amendments didn’t mention race, but were enforced unequally. Black Americans were far more often than white Americans forced to pay fees known as “poll taxes,” subjected to “literacy tests” and forced to answer questions like “how many bubbles are in a bar of soap?” So, Black women like journalist Ida B. Wells set up suffrage clubs to teach Black people what to expect when they went to vote. Sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer, who was in her 40s when she learned she could vote, criss-crossed the country helping others do the same.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 made many of the Jim Crow era-obstacles to voting illegal. But the fight to preserve its teeth continues. In 2013, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling weakened federal oversight of state voting laws. Today, people in predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods face longer lines to vote and a shrinking number of polling places.

In spite of those challenges, former Georgia House minority leader Stacey Abrams and activists like Nsé Ufot, CEO of the New Georgia Project, are among the voting rights activists who helped register more than 800,000 new Georgia voters since Abrams lost the governor’s race in 2018. Their efforts, and Black voter turnout, are credited with Georgia voting for a Democratic candidate for President for the first time since 1992.

“You don’t win the right to vote and then that’s just it,” Ufot says of the lessons from the history of voting rights activism. “Throughout the course of history for every expansion of voting rights that brings in more people, we have a corresponding contraction, or corresponding backlash, that seeks to make it more difficult for people to vote, that seeks to shrink the electorate and shrink the number of people that participate in our democracy.”

0 Comments